Are you sure they have wings?

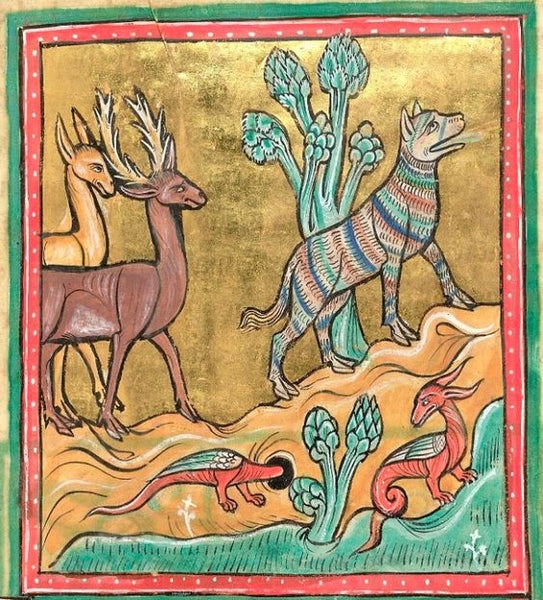

Image of a panther from the Rochester Bestiary

In our previous post we looked at how ancient man mystified certain animals with a hefty dose of romanticism and misplaced judgement, and also how they used their imaginative interpretations as key characters in their stories of legend and folklore. In this edition we will look at how previously unfamiliar animals were introduced in to popular culture, and how in some cases man's imagination occasionally filled the gaps, resulting in some slightly odd portrayals.

As the all-concurring Romans returned home from beyond the borders of Europe, they brought with them many new exotic and ferocious animals. The scaly, furry, and feathered cargo symbolised their concurring achievements, and what better idea than to bring them back to Rome and show them off in the Coliseum: where monkeys were dressed up as soldiers riding goat powered chariots, and starving lions would tear apart some troublesome Christians. Or even better, you could use them in battle! This is exactly what they did with the mighty and majestic elephant, whose sorts were actually used like trumpeting tanks; mainly to scare the living daylights out of the poor heathens who had never seen anything quite like an elephant before - they must have been terrified: lord only knows what tales the survivors told!

The fall of Rome led Europe in to an era of ignorance known as the Dark Ages, with the accumulated knowledge of the ancient world temporally lost. But by the 12th Century is was decided in Britain that an animal encyclopaedia (of sorts) should be created: and so, using the Greek scriptures of Physiologus as a source, the church set to work in Rochester Cathedral to create a 'moralised' collection of drawings and descriptions of beasts. The result was the medieval Rochester Bestiary, famous for its fanciful portrayal of animals: such subjects include a multicoloured Panther, a bizarre looking fox which lures its prey by playing dead, and hedgehogs who roll around in grapes which then stick to their spines so they can carry them off for their young - I think Daniel's Hedgehog at Night may have done the same thing with blackberries!

And then we have German painter, Albrecht Dürer, who in the year 1515 was given a written description and a brief sketch of a rhinoceros. Even though Dürer had never seen a rhino before, he set about creating a woodcut rendition of this specimen using what little information he had. It was a good effort, but Dürer must have thought that the rhino needed some small modifications, such as plate-like armour, and a little spare horn which sat on the small of the creatures back - perfect to grab ahold of if you were riding one! Europe gave Dürer's rhino the thumbs-up, and copies and reproductions of his rendition circulated around the continent for the next 300 years!